What happens when a powerful ruler adopts a new religion that contradicts the life into which he was born? What about when this change occurs during the height of his rule when things are pretty much going his way? How is that information conveyed over a large geographical region with thousands of inhabitants?

King Ashoka, who many believe was an early convert to Buddhism, decided to solve these problems by erecting pillars (Ashok Stambh) that rose some 50’ into the sky. The pillars were raised throughout the Magadha region in the North of India that had emerged as the center of the Indian empire, the Mauryan Dynasty (322-185 B.C.E). Written on these pillars, intertwined in the message of Buddhist compassion, were the merits of King Ashoka.

The third emperor of the Mauryan dynasty, Ashoka (pronounced Ashoke), who ruled from c. 279 B.C.E. – 232 B.C.E., was the first leader to accept Buddhism and thus the first major patron of Buddhist art. Ashoka made a dramatic conversion to Buddhism after witnessing the carnage that resulted from his conquest of Kalinga. He adopted the teachings of the Buddha known as the Four Noble Truths, referred to as the dharma (the law):

Life is suffering (suffering=rebirth)

the cause of suffering is desire

the cause of desire must be overcome

when desire is overcome, there is no more suffering (suffering=rebirth)

Individuals who come to fully understand the Four Noble Truths are able to achieve Enlightenment, ending samsara, the endless cycle of birth and rebirth. Ashoka also pledged to follow the Six Cardinal Perfections (the Paramitas), which were codes of conduct created after the Buddha’s death providing instructions for the Buddhist practitioners to follow a compassionate Buddhist practice. Ashoka did not require that everyone in his kingdom become Buddhist, and Buddhism did not become the state religion, but through Ashoka’s support, it spread widely and rapidly.

Ashoka pillar at Vaishali, Bihar, India

The pillars

One of Ashoka’s first artistic programs was to erect the pillars that are now scattered throughout what was the Mauryan empire. The pillars vary from 40 to 50 feet in height. They are cut from two different types of stone—one for the shaft and another for the capital. The shaft was almost always cut from a single piece of stone. Laborers cut and dragged the stone from quarries in Mathura and Chunar, located in the northern part of India within Ashoka’s empire. The pillars weigh about 50 tons each. Only 19 of the original pillars survive and many are in fragments. The first pillar was discovered in the 16th century.

Lotus and lion

The physical appearance of the pillars underscores the Buddhist doctrine. Most of the pillars were topped by sculptures of animals. Each pillar is also topped by an inverted lotus flower, which is the most pervasive symbol of Buddhism.

A lotus flower rises from the muddy water to bloom unblemished on the surface—thus the lotus became an analogy for the Buddhist practitioner as he or she, living with the challenges of everyday life and the endless cycle of birth and rebirth, was able to achieve Enlightenment, or the knowledge of how to be released from samsara, through following the Four Noble Truths.

This flower, and the animal that surmount it, form the capital, the topmost part of a column. Most pillars are topped with a single lion or a bull in either seated or standing positions. The Buddha was born into the Shakya or lion clan. The lion, in many cultures, also indicates royalty or leadership. The animals are always in the round and carved from a single piece of stone.

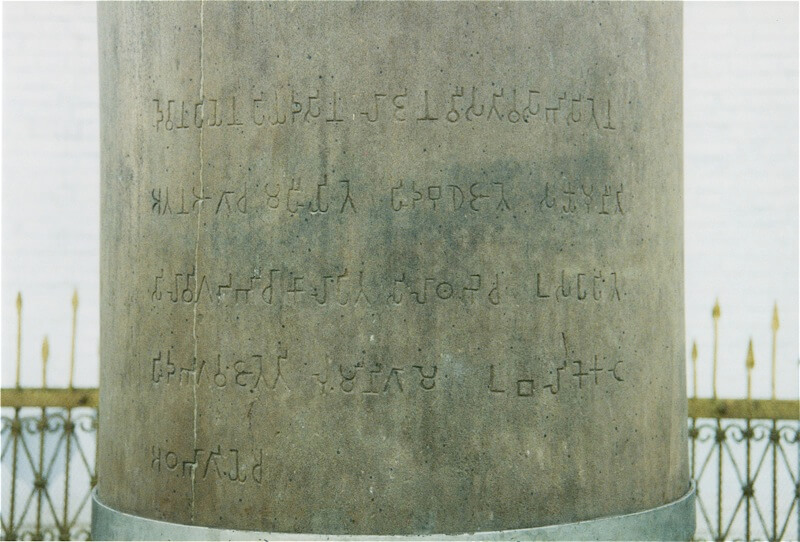

The edicts

Some pillars had edicts (proclamations) inscribed upon them. The edicts were translated in the 1830s. Since the 17th century, 150 Ashokan edicts have been found carved into the face of rocks and cave walls as well as the pillars, all of which served to mark his kingdom, which stretched across northern India and south to below the central Deccan plateau and in areas now known as Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

The rocks and pillars were placed along trade routes and in border cities where the edicts would be read by the largest number of people possible. They were also erected at pilgrimage sites such as at Bodh Gaya, the place of Buddha’s Enlightenment, and Sarnath, the site of his First Sermon and Sanchi, where the Mahastupa, the Great Stupa of Sanchi, is located (a stupa is a burial mound for an esteemed person. When the Buddha died, he was cremated and his ashes were divided and buried in several stupas. These stupas became pilgrimage sites for Buddhist practitioners).

Ashoka Pillar at Lumbini, Nepal, the birthplace of the Buddha

Some pillars were also inscribed with dedicatory inscriptions, which firmly date them and name Ashoka as the patron. The script was Brahmi, the language from which all Indic language developed. A few of the edicts found in the western part of India are written in a script that is closely related to Sanskrit and a pillar in Afghanistan is inscribed in both Aramaic and Greek—demonstrating Ashoka’s desire to reach the many cultures of his kingdom. Some of the inscriptions are secular in nature. Ashoka apologizes for the massacre in Kalinga and assures the people that he now only has their welfare in mind. Some boast of the good works that Ashoka has done, underscoring his desire to provide for his people.

The Hinayana period

Lion Capital of Ashoka, Sarnath

The pillars (and the stupas) were created in the Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle) period. Hinayana is the first stage of Buddhism, roughly dated from the sixth c. to the first century B.C.E., in which no images of the Buddha were made. The memory of the historical Buddha and his teachings was enough to sustain the practitioners. But several symbols became popular as stand-ins for the human likeness of the Buddha. The lotus, as noted above, is one. The lion, which is typically seen on the Ashokan pillars, is another. The wheel (chakra) is a symbol of both samsara, the endless circle of birth and rebirth, and the dharma, the Four Noble Truths.

Why a pillar?

There are a few hypotheses about why Ashoka used the pillar as a means for communicating his Buddhist message. It is quite possible that Persian artists came to Ashoka’s empire in search of work, bringing with them the form of the pillar, which was common in Persian art. But is also likely that Ashoka chose the pillar because it was already an established Indian art form. In both Buddhism and Hinduism, the pillar symbolized the axis mundi (the axis on which the world spins).

The pillars and edicts represent the first physical evidence of the Buddhist faith. The inscriptions assert Ashoka’s Buddhism and support his desire to spread the dharma throughout his kingdom. The edicts say nothing about the philosophical aspects of Buddhism and scholars have suggested that this demonstrates that Ashoka had a very simple and naïve understanding of the dharma. But, as Ven S. Dhammika suggests, Ashoka’s goal was not to expound on the truths of Buddhism, but to inform the people of his reforms and encourage them to live a moral life. The edicts, through their strategic placement and couched in the Buddhist dharma, serve to underscore Ashoka’s administrative role and as a tolerant leader.

Edict #6 is a good example:

Beloved of the Gods speaks thus: Twelve years after my coronation

I started to have Dhamma edicts written for the welfare and happiness of the people, and so that not transgressing them they might grow in the Dhamma. Thinking: “How can the welfare and happiness of the people be secured?” I give my attention to my relatives, to those dwelling far, so I can lead them to happiness and then I act accordingly. I do the same for all groups. I have honored all religions with various honors. But I consider it best to meet with people personally.